About Shaped-Note Singing

and

The Christian Harmony

~*~

The Christian Harmony, 2010 edition

A new edition of The Christian Harmony was published in 2010. It is a combination of the "Carolina Book" and the "Alabama Book". Supplies of both books had run out, and reprinting was essential to keep the tradition alive. It seemed best to combine forces and resources. The 2010 edition uses Aikin shapes.

The Christian Harmony, Folk Heritage edition, 2015

There was interest and desire to see a reprint of William Walker's book retaining Walker's original shapes, words, and notes. In 2015 Zack Allen and Folk Heritage of North Carolina published a facsimile edition of the 1873 The Christian Harmony,

~*~

The two versions of Christian Harmony that made the 2010 edition

with a short history of shaped-note singing

Shaped-note singing began in the late 1700's as a teaching device in American

singing schools in the Northeastern United States. People were looking for

a way to make singing arts more accessible. Shapes were added to the note

heads in written music to help singers find pitches within major and minor

scales without the use of more complex information found in key signatures

on the staff. This sight-reading device really worked ... and still works

today.

Tunes were written for a capella singing in dispersed harmony and printed in oblong tune books. The first shape systems were based on the old English solfege syllables FA-SOL-LA-FA-SOL-LA-MI-FA for the major scale so only four shapes were needed.

As settlers began to move westward, down through the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, southward along the Appalachian Mountains, and into the frontier areas of Tennessee, The Carolinas, and Georgia, they took tune books with them.

The shaped-note idiom was very instructive and useful for people who had little time for lengthy academic careers; settling a new country was certainly more of a priority. The four-shape, or FA-SOL-LA system, as it is sometimes called, along with the whole concept of singing schools was above all portable.

In the mid-nineteenth century, however, several American tunesmiths and compilers began to experiment with the Italian solfege and added shapes to fit a DO-RE-MI-FA-SOL-LA-SI-DO, major-scale pattern. William Walker of Spartanburg, South Carolina was one of these creative types.

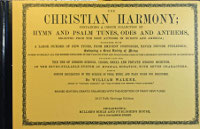

Walker, already a singing school master of note and the compiler of The Southern Harmony (1835), invented his own seven-shape system, and in 1866 published the first edition of The Christian Harmony.

The book primarily used in Western North Carolina today is a reprint edition of the 1873 edition published by Walker. The only revision of this book is some additional academic material and commentary at the beginning, four songs added in an appendix at the end, and some additional indexes appended to the older ones. So we are really using unrevised songs in arrangements that were actually sung nearly 130 years ago.

Many of the songs are actually much older than that, dating back to the eighteenth century or before, and still written in the original dispersed harmonies (each part written on a separate staff).

Some people confuse this music with gospel music, which actually came later in the late 1800's. A number of Walker's selections in the Christian Harmony are of an early gospel or proto-gospel flavor, but most harmonies still retain the original character of polyphony where each part is a sort of melody in itself harmonizing with the other parts instead of the more modern gospel song concept wherein the harmonies occupy a narrower range of possibilities.

The whole shaped-note system makes the more complicated harmonic parts easier to sing by sight reading. Therefore, at a singing, you may be surprised to hear ordinary people sing what seems at times to be very complicated arrangements only a trained choir might attempt.

It might also sound odd to hear many songs that are in a minor key or even modal. Much of the singing may sound to some like Medieval or Celtic music, and with good reason...it's old, and much of it has its roots in Western European folk styles and in musical genres of the Protestant Reformation.

Even though most of the copies of books you will see are of a newer printing, there are singers who arrive to sing from old books owned by a relative or another singer who has passed away. This is just another sign of the age and continuity of the tradition.

About the "Alabama Book"

Just to clear up a little confusion that may follow, there are two editions of The Christian Harmony in use today. The edition mostly used in Alabama and Georgia is the 1994 revision of the Deason-Parris revision of 1958. It is also sometimes referred to as the "Black Book" because the 1958 book was published with a black cover (The 1994 revision has a brown cover.)

This book was revised in 1958 to utilize Jesse Aikin's seven-shape note system that became well-known among gospel singers in the South. This system is actually older than Walker's 1866 system by about twenty years.

The Deason-Parris revision also deletes a number of songs from the Walker book but includes other songs not found in the 1873 edition. Some of these songs are also associated with the Sacred Harp tradition found strongest in Georgia, Alabama, and some other parts of the South.

Each book represents a vibrant singing tradition -- living tradition that is more about people than books.

Often at singings you may notice that a song leader may select songs to lead from both books. Sometimes singings tend toward the use of one book or the other, but we seem to value our diversity without insisting on uniformity, and somehow we come out with an enriching kind of unity.

by Larry Beveridge, c. 2001